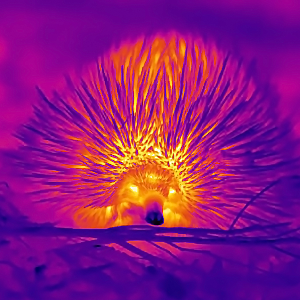

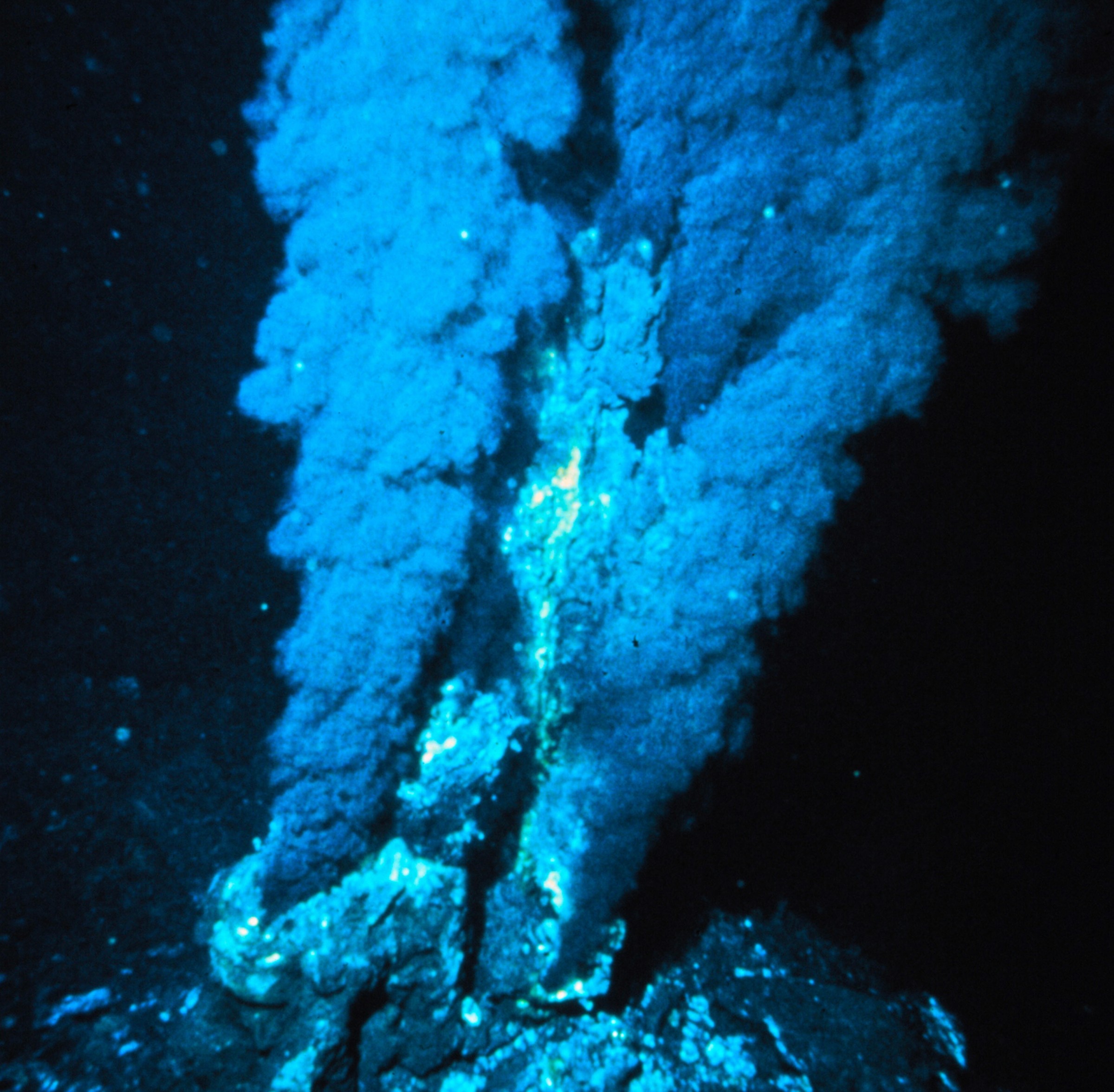

10 creatures that defy heat

From hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor to the deserts on all five continents: Life thrives even in the hottest places on our planet. Evolution has produced adaptation strategies that are as diverse as they are astonishing. We present ten organisms and their tactics for dealing with heat.