Devastation, shortages, hunger, all in the somber shadow cast by the country’s National Socialist past. How could academic life even exist under such conditions? Where and how is our knowledge of LMU in the post-war period stored? And what can we learn from this time?

In search of answers to these questions, trainee teachers at LMU and pupils at a Munich high school delved deep into the University’s past. They trawled through whole boxes of files. Leafed through folders and photographs. Deciphered original texts – and were astonished at what they found in the University archive.

Authentic source material

Their research was overseen by two experts: senior lecturer Daniela Andre of the Munich History Lecture, and Dr. Susanne Wanninger of the University Library. “Digging into history, rummaging through archives – that all sounds a bit dry and dusty when you first mention it,” Andre says. “But the children were really excited. They discovered things that nobody knew. And the students learned how to develop an exhibition project: leaving the outcome open, working collaboratively and drawing on authentic source materials.”

The relevant files were reviewed out of a total inventory of 411 archive boxes – none of which have yet been fully explored, as Wanninger explained. This made it all the more exciting to discover what lay hidden in boxes that were once carefully crafted by a book binder but have long since been replaced by off-the-shelf cardboard versions.

Surprising finds

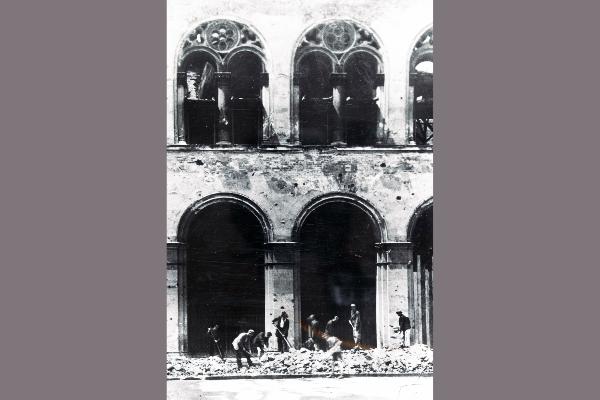

Not everything unearthed by this research was new. It was already known that, between 1946 and 1949, students had to work in crews to remove rubble before they could begin their studies. Other finds came as a surprise even to the experts: One was the curious fact that medical students complained of a lack of corpses – a bottleneck Wanninger believes was due to the need to catch up with all the prep courses that had been missed. Another was that, after the end of the war, LMU supervised would-be medics not only in Munich but also in Regensburg.

The value of sources in understanding history

“It was fascinating to hold original documents and photos in my hands, and to work with them myself,” says trainee teacher Amelie Stockburger. “I discovered just how much you can learn about individual fates and history in general by working in an archive. And I learned how valuable such sources are for our understanding of history.”

Sixteen-year-old Mareike of the Lise-Meitner-Gymnasium in Unterhaching was also very moved by the aging documents: “Quite unexpectedly, we found a file in which a murder was described like a crime thriller,” she says.

Léana, aged 17, took part in the course to learn more about the end of the Holocaust and about reconstruction. Her comment: “Leafing through yellowing documents, many of them written on a typewriter, gave me a more vivid and tangible feel for the post-war era.”

Exciting exhibits shed light on the past

The fruit of their research is now on show in twelve display cases. The exhibits include many exciting original documents that shed light on those dark years: photos of the destroyed main University building, for example; sketched biographies of two forced laborers who were killed, and whose bodies were used by the Faculty of Medicine; documents dealing with the revocation of academic titles for former Nazis; and letters penned by Jewish students and professors who, after emigrating, struggled to have their academic achievements recognized – and who were given short shrift by the University administration. “For us, the exhibition is a chance to give visibility to the materials in our possession,” Wanninger says. “There is so much potential in this stuff!”

So much potential!

Just how important it is – especially today – to introduce young people to archive work is spelled out by Professor Michele Barricelli, Chair of Historical Didactics and Public History: “Without documents, without research, without sources, you will never have historical knowledge,” he says, adding that, in the age of social media and fake news, these skills are more important than ever. Nor is learning historical facts the only thing: It is also about “your own connection to what happened back then.” Projects such as this one, he explains, help trainee teachers learn how to introduce the pupils they will one day teach to a past “that seems to be becoming more and more distant and harder to understand”.

The exhibition “Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in the post-war era” is open from 29 April to 11 July 2025 at the University Library, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1. It is part of a program entitled “1945 | 2025 – Zero hour? How we became what we are”, initiated by the City of Munich’s Department of Culture.