Dear children, I wanted to quickly send you [...] my love from the fortress I currently find myself in. The state police have put the government building housing the Commissariat-General on defense alert to prevent any attempts to raid it. A strange state of affairs. During the revolution in 1918 and during the Soviet period in 1919, the government building stood free and open. There were wild demonstrations by the left. Today the building must be protected against attacks by the right, even though it houses a right-wing government. [...]

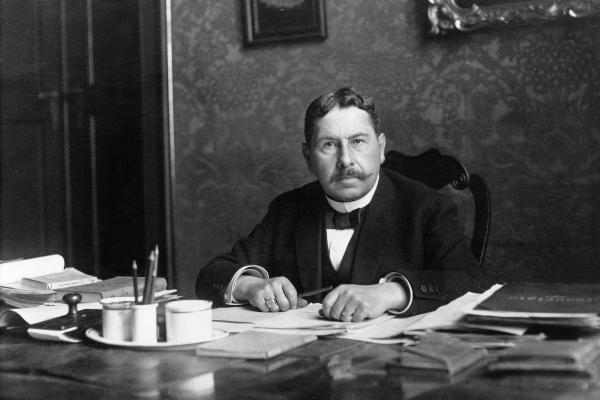

These are the words of right-wing conservative civil servant and politician Gustav von Kahr, writing to his daughter and son-in-law on 19 November 1923. As Commissioner-General of Bavaria with quasi-dictatorial powers, he had had the attempted coup staged by Hitler and Ludendorff put down ten days earlier, incurring the wrath of nationalists. After all, von Kahr had agreed to support Hitler at the beginning of the putsch – but only under pressure from Hitler himself. The Nazi leader had had his Stormtroopers storm a meeting in Munich’s Bürgerbräukeller on 8 November, where von Kahr was giving a speech. Hitler took to one side the three representatives of state power who were present — besides von Kahr, these were Hans von Seißer, head of the state police, and Otto von Lossow, commander of the Reichswehr in Bavaria — and demanded of them at gunpoint that they support the putsch.

Chronology in 15-minute increments

The recently published new edition, Generalstaatskommissar Gustav von Kahr und der Hitler-Ludendorff-Putsch (State Commissioner-General Gustav von Kahr and the Beer Hall Putsch), shows what happened before and after the putsch, up until von Kahr’s violent death in Dachau concentration camp in 1934, using previously unpublished original documents written by von Kahr himself. The editor is Dr. Matthias Bischel, research associate at LMU’s Institute for Bavarian History. He has traced the events in detail based, among other things, on evidence found in von Kahr’s private estate.

“My aim was to edit all relevant documents written by the man himself and those immediately around him in a chronologically structured manner in order to be able to understand how the portrayal of the putsch developed over time,” says Bischel. The researcher painstakingly compared von Kahr’s documents against sources from other tellings of the story in order to verify their validity. The historian presents the events from the start of the Bürgerbräu meeting on the evening of 8 November until the order is given to the Reichswehr and state police to suppress the putsch the following morning, for example, in a tabular chronology in 15-minute increments. One column documents the actions of von Kahr himself, the other presents the key events surrounding him. “Taking this into account, von Kahr’s version is essentially confirmed,” says Bischel.

Seven boxes of personal effects

A total of seven boxes of documents, which the Institute was given by the heirs of the former district president of Upper Bavaria, Bavarian Minister-President and State Commissioner-General, were made available to Bischel for his research. Not only do they record the events surrounding the attempted putsch, they also document von Kahr’s actions in the subsequent court case and, above all, show that his description of the events remained essentially unchanged until his death. Thus, contrary to what one might expect, there were no modifications of his memory that cast the events in a different light. “As early as 4 December 1923, von Kahr had to testify as a witness before the public prosecutor,” explains Bischel. “This was one of the reasons why he prepared his version of events before the putschists gave their testimony, and then, of course, he had to stick to it for the sake of his credibility. All the more so as entire passages from his account were reproduced several times not only in the indictment but also in the media — probably due to von Kahr’s influence.”

The statesman self-image

While previous essays on the attempted putsch of 1923 have focused primarily on Hitler and Ludendorff, Bischel’s work sheds light on the representatives of the state, in particular of course on Gustav von Kahr. The historian, in his dissertation, had already delved into the biography of this statesman, who was never able to shake off the stigma of being called a traitor, as the Nazis labeled him after the putsch. However, according to what we now know, there are numerous indications that von Kahr was keen to fight the attempted putsch from the outset — as Bischel concludes from his research. Von Kahr’s aim was instead to facilitate the formation of a Reichsdirektorium in Berlin — a Reich government that bypasses parliament — which at least had a semblance of legality. To this end, he had already established contacts with other right-wing figures in Germany.

According to Bischel, von Kahr was never a politician in the modern sense of the word. Although a pro forma member of the Bavarian People’s Party, he had always cultivated the self-image of being a non-partisan, ‘neutral’ statesman. The extent to which he apparently transferred this same image onto other political decision-makers and how much he thus underestimated Hitler was shown, for example, in a letter he wrote to the Reichskanzler himself on 10 April 1934 from his retreat in Unterwössen in Chiemgau. Posters had already been put up there defaming him as a traitor several times. Fireworks were even set off in his front garden. In the letter, he asked Hitler to try to prevent these attacks: “[...] I am firmly convinced that you, Herr Reichskanzler, by no means approve of those incidents in Unterwössen and that you will take steps to put a stop to such unworthy machinations, which are aimed at making me homeless and, so to speak, outlawed.” He never received a reply. Gustav von Kahr was shot eleven weeks later in Dachau concentration camp.

Matthias Bischel:Generalstaatskommissar Gustav von Kahr und der Hitler-Ludendorff-Putsch (State Commissioner-General Gustav von Kahr and the Beer Hall Putsch)

Documents pertaining to the events of 8/9 November 1923

Publication series on Bavarian regional history, volume 178 Verlag C.H. Beck, 2023